Camac Blog

Constance Luzzati, French baroque and the concert harp

Latest

February 14, 2022

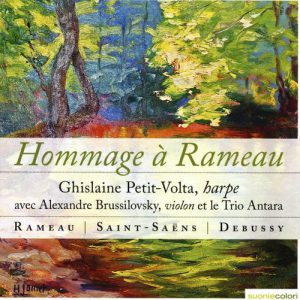

Constance Luzzati is crowdfunding an album entirely dedicated to Rameau on the harp. Recorded on the Paraty label, it will be the latest in a growing body of work on harp transcriptions. We have contributed and the fundraising is continuing here until the end of February.

Sir Thomas Beecham famously decreed that “A musicologist is a man who can read music but cannot hear it.” Perhaps he had a point in 1940…fortunately, the perplexing chasm between music theory and performance practice is receding, thanks to the work of artists who do both.

Constance Luzzati is an alumna of the demanding dual Sorbonne · CNSM musicology and performance course, and fell in love with baroque music during musicology lectures. “Performers want to play music they would also like to go and listen to in a concert, so I then wanted to play more baroque literature on the harp”, she explains. She began transcribing Frescobaldi, before moving to later baroque. “It’s too early for an equal-tempered instrument like the modern harp”, she explains. “I enjoy playing continuo on early harps, but I didn’t want to change my own solo instrument. So I looked for something else, focusing on the 18th century because firstly there is a lot more accessible repertoire than from the 17th, and secondly to avoid these temperament issues. This was how I came to write my doctoral thesis on 18th century French baroque, performed on the modern harp.”

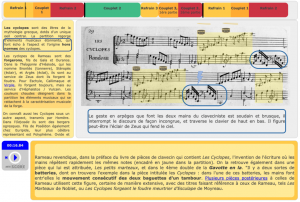

With a musicological and practical methodology from the outset, reading through the literature at the harp sharpened Constance’s focus on Rameau. Couperin, Dulphy and Royer were musically inspiring, but “didn’t work as well. I love playing their music and it pushes the harpist to their limits, and some adaptation is unavoidable.” In this video, 2’50, Constance provides an entertaining illustration of where Royer’s Vertigo may be forever clavecin. “What I also love about Rameau”, she continues, “is how his music is highly contrasted, but it’s never over-stylised, he doesn’t indulge in mannerisms. Whether it’s a poetic, reflective work like Les Soupirs, Entretien des muses or Rappel des oiseaux, or a theatrical one like Les Cyclopes, or a more abstract piece like an allemande, his powerful musical intellect underpins everything and that makes his music very satisfying to perform and to listen to.”

Working with the harpsichordist Kenneth Weiss as well as Isabelle Moretti, Constance embarked on both technical and stylistic directions that were, initially, a foreign language to a concert harpist. Like learning languages, they also brought new insight. “We train our gestures for years to do things like big arpeggios racing up and down the harp, but we struggle to play even small ornaments with the left hand. Baroque ornaments belong to all voices, and they are phrased and part of the melodic and rhythmic logic, so you can’t leave them out. The resonance of the modern harp is another tricky point. I think the clear timbre of the modern French harps is beautiful for this music, but you need to bring that out with specific techniques, like damping note-by-note while playing without losing the arc of the phrase. There’s also stylistic questions like how to manage uneven rhythms, which are not like modern dotted rhythms. All of this is possible, but it isn’t in our DNA, it’s not our mother tongue.

That said, the comparison with translation is only partial, because translation is instantly legitimate. You have to translate for a new audience to understand information. Nobody contests that, and broadly the translator does their work to serve that audience. In music, you can simply choose to attend a harpsichord concert instead of a harp one, so the transcription serves performers as much as listeners. Is that legitimate?

The legitimacy of transcriptions is commonly challenged via questions of authenticity. Not that we will ever know what Rameau really sounded like in 1725…but anyway, in a 21st-century context I think in terms of fidelities (in the plural) rather than authenticity. For sure, if you can play something without changing it, I don’t see the interest in changing a note of the score. I’m not a composer, I’m looking for music to play, not rewrite. But some changes in transcriptions are necessary, some are even desirable. You might need to do it to be faithful to the musical spirit. If you played the Urtext, that spirit could actually get lost because of technical difficulties. Literary translation has to make those kinds of judgments as well, between precision and meaning, fidelity and idiomacy. There’s plenty of pieces I love but I haven’t yet found a faithful and playable solution for. So I’m not playing them at the moment.”

Transcription also evokes an interesting question of legitimate instruments. Dominant instruments have vast repertoires, and this question is challenging for the harp. There are good original pieces that deserve to be better known, and (to this end) more courageously programmed by mainstream promoters. There are also other things that can be done about it.

“Given that this core repertoire is compact”, Constance argues, “there are two principal channels to expand it further. One is transcription, and the other is new music. Interestingly, it’s often the same people who take an interest in both…I’m not sure why that is, but I do believe that presenting incredible music – new or old – helps liberate the harp from its niche. The market among the general public for repertoire by Parish-Alvars and his contemporaries certainly exists but is forcibly limited, regardless of how well this repertoire is played. Nor can we all spend our lives performing Fauré, Caplet, Debussy and Hindemith on loop. It’s a pity if this repertoire limitation spills over onto our instrument. On the contrary, transcription is an opportunity to establish a virtuous circle. The better and more extensive the repertoire and the more legitimate the harp, the more fine works will be written for it because good composers will sit up and take notice. This is already happening: more and more excellent composers are interested in the harp. I believe that transcription serves our instrument, and also expands the interpretative possibilities for the transcribed pieces themselves because it brings new colours and ways of listening to the text.”

If this has caught your own interest, you can:

• Support Constance’s crowdfunding!

• Enjoy her Jeudi classique YouTube concert, recorded for us at the height of Covid-19 lockdowns

• Listen to more Rameau that wasn’t part of her Youtube concert: l’entretien des muses

• If you speak French, check out her brilliant interactive guide to Rameau’s Les Cyclopes

• Continue the discussion in the comments section below!

• Email your questions, thoughts and feedback to [email protected].